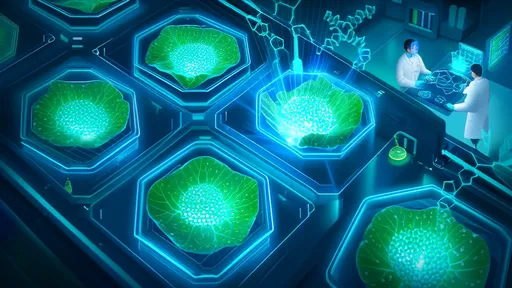

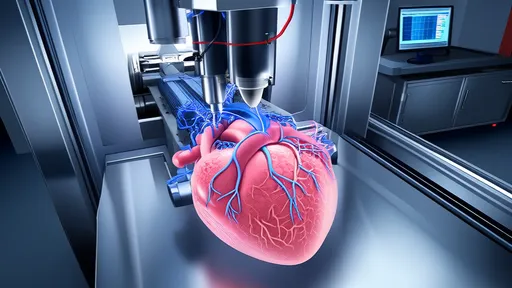

The concept of 3D printing has revolutionized manufacturing, but its application in biology—particularly in constructing artificial organs from stem cells—has opened a new frontier in medical science. Dubbed the "3D bioprinter," this technology leverages the unique properties of stem cells to build functional tissues layer by layer. Unlike traditional 3D printers that use plastics or metals, bioprinters employ bioinks composed of living cells, growth factors, and biomaterials. The implications for regenerative medicine are staggering, offering hope for patients awaiting organ transplants and paving the way for personalized healthcare solutions.

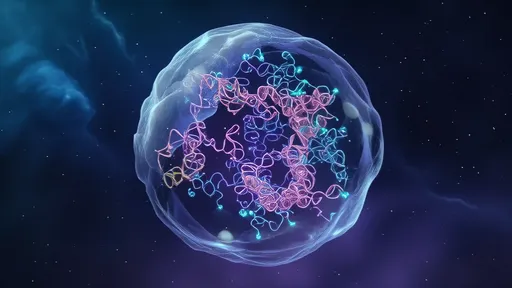

At the heart of this innovation lies the versatility of stem cells. These undifferentiated cells have the remarkable ability to develop into specialized cell types, making them ideal for constructing complex tissues. Scientists can now direct stem cells to differentiate into heart, liver, or kidney cells before arranging them into precise three-dimensional structures. The bioprinter acts as a meticulous architect, depositing cells in patterns that mimic natural organ architecture. This level of precision was unimaginable a decade ago, but today, researchers are inching closer to creating lab-grown organs that could function seamlessly in the human body.

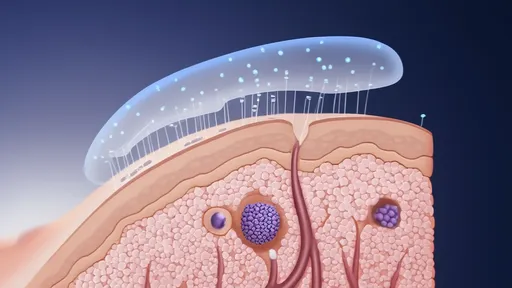

One of the most significant challenges in bioprinting is ensuring the survival and integration of printed tissues. Cells require a constant supply of oxygen and nutrients, which in natural organs is provided by an extensive network of blood vessels. To address this, scientists are developing techniques to print vascular networks alongside organ tissues. Recent breakthroughs include the creation of rudimentary blood vessels using a combination of endothelial cells and supportive biomaterials. While these structures are not yet capable of sustaining large organs, they represent a critical step toward achieving fully functional artificial organs.

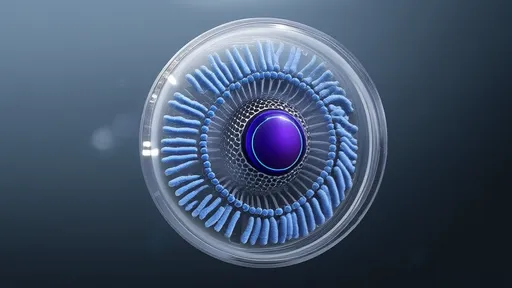

The potential applications of stem cell-based bioprinting extend beyond transplantation. Pharmaceutical companies are increasingly using 3D-printed tissues for drug testing, reducing reliance on animal models and improving the accuracy of toxicity screenings. These lab-grown tissues can replicate human physiology more closely than traditional methods, allowing researchers to predict drug responses with greater fidelity. In one notable example, bioprinted liver tissue was used to test the metabolic effects of a new drug, yielding results that closely mirrored outcomes observed in human trials.

Ethical considerations, however, loom large over this burgeoning field. The use of embryonic stem cells, though highly effective, remains controversial. Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which are reprogrammed from adult cells, offer a morally neutral alternative, but their long-term stability and safety are still under investigation. Regulatory frameworks are struggling to keep pace with the rapid advancements in bioprinting, leaving gaps in oversight that could lead to misuse. Striking a balance between innovation and ethical responsibility will be crucial as the technology matures.

Looking ahead, the convergence of bioprinting with other cutting-edge technologies like artificial intelligence and CRISPR gene editing could accelerate progress. AI algorithms can optimize printing parameters to enhance cell viability, while CRISPR may allow scientists to tweak stem cell genomes for improved functionality. Some researchers envision a future where patients receive bespoke organs engineered to resist rejection or even combat disease. Though such scenarios remain speculative, the groundwork is being laid today in labs around the world.

Despite the excitement, significant hurdles remain. Scaling up from small tissue patches to full-sized organs requires advances in both bioprinting speed and the scalability of bioink production. The immune system’s response to artificial tissues also poses a challenge, as even minor incompatibilities could trigger rejection. Collaborative efforts between biologists, engineers, and clinicians are essential to overcome these obstacles. Institutions like the Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine have already demonstrated promising results with bioprinted skin and cartilage, fueling optimism for more complex organs.

The economic implications of successful organ bioprinting are equally profound. The global organ transplant market, burdened by shortages and exorbitant costs, could be disrupted by lab-grown alternatives. A single bioprinter, though expensive initially, could theoretically produce countless organs over its lifespan, dramatically reducing costs and wait times. Health insurers and governments are closely monitoring these developments, anticipating a future where organ failure is no longer a death sentence but a treatable condition.

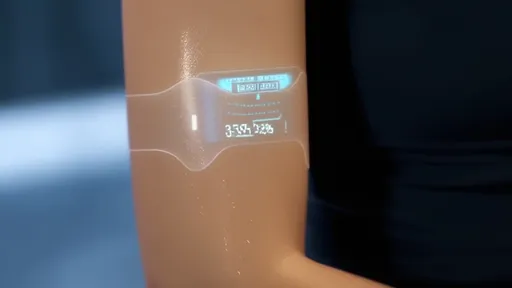

Public perception will play a pivotal role in the adoption of bioprinted organs. While the technology promises to save lives, it also evokes science-fiction imagery that may unsettle some. Transparent communication about the science, benefits, and limitations of bioprinting will be essential to garnering trust. Educational initiatives aimed at demystifying the process—such as illustrating how a patient’s own cells can be used to create a compatible organ—could alleviate concerns and foster acceptance.

In the coming years, the field will likely see incremental improvements rather than sudden breakthroughs. Each small step—whether it’s extending the lifespan of bioprinted tissues or improving vascularization—brings us closer to the ultimate goal. The vision of a world where no patient dies waiting for a donor organ is no longer the stuff of fantasy. With continued investment and interdisciplinary collaboration, the 3D bioprinter may well become as commonplace in hospitals as MRI machines are today.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025