In recent years, universities across the country have been embracing an innovative approach to environmental education—the installation of miniature constructed wetland systems on campus grounds. These scaled-down replicas of natural wetlands serve not only as functional water purification systems but also as living laboratories for students studying ecology, environmental science, and sustainable design.

The concept originated from environmental engineering departments seeking more hands-on teaching tools. Unlike traditional classroom models or computer simulations, these operational wetland systems allow students to observe phytoremediation processes in real-time. From the initial sedimentation tanks to the final outflow channels, every purification stage becomes a tangible learning experience.

What makes these campus wetlands particularly remarkable is their dual functionality. While processing greywater from nearby buildings (typically 500-1,000 liters daily), they simultaneously create microhabitats for local biodiversity. Dragonflies hover above the water surface, aquatic plants filter contaminants, and microbial communities thrive in the gravel substrate—all within view of lecture halls and dormitories.

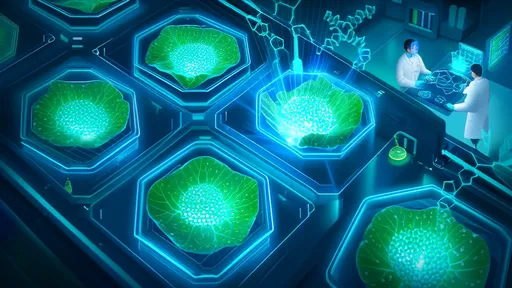

The typical setup involves three treatment zones: an anaerobic section with submerged plants, an aerobic flow-through area featuring emergent vegetation like reeds and rushes, and finally a polishing zone with floating species such as water hyacinths. This configuration mirrors full-scale constructed wetlands used in municipal wastewater treatment, just condensed to classroom-friendly dimensions.

Students participate in every phase, from designing the hydraulic loading rates to monitoring water quality parameters. Chemistry majors test for BOD and nitrogen levels, biology students document species colonization patterns, while environmental policy concentrators analyze regulatory frameworks for such nature-based solutions. The interdisciplinary nature of these projects has made them particularly valuable for capstone courses.

Beyond academic applications, these systems have become campus landmarks. Several universities have incorporated them into sustainability tours, showing prospective students and visitors how ecological principles translate into practical engineering solutions. The visual appeal of lush vegetation and clear water provides a stark contrast to conventional storm drains, making the invisible process of water purification suddenly visible and comprehensible.

Maintenance presents its own educational opportunities. Student teams rotate responsibilities for removing accumulated sediments, pruning vegetation, and testing water quality. These routine tasks teach valuable lessons about the ongoing commitment required for environmental stewardship—lessons that textbook diagrams simply cannot convey.

The technology's adaptability has allowed for creative variations. Some institutions have built vertical-flow wetlands to demonstrate space-efficient designs, while others incorporate solar-powered pumps to highlight renewable energy integration. One Midwestern university even designed a mobile wetland unit on a trailer, allowing demonstrations at local schools and community events.

Perhaps most importantly, these micro-wetlands reshape how students perceive wastewater. Seeing kitchen runoff transform into habitat-supporting water through natural processes fosters a profound appreciation for circular systems. Many participants report changed water usage habits after witnessing how their daily actions impact treatment systems.

As climate adaptation becomes increasingly urgent, such hands-on experiences with nature-based solutions prepare the next generation of environmental professionals. Graduates who trained on these systems now implement full-scale wetlands in developing countries, urban parks, and industrial sites—carrying lessons from their campus miniature into the wider world.

The initiative hasn't been without challenges. Early adopters struggled with winter operation in northern climates until they implemented greenhouse enclosures. Other institutions faced initial skepticism about dedicating precious campus space to what some administrators viewed as "glorified ponds." However, the measurable educational outcomes and positive community response have converted most critics into supporters.

Looking ahead, several universities are exploring augmented reality integrations. By scanning QR codes near the wetland, visitors can access real-time water quality data, 3D visualizations of subsurface processes, and interviews with student researchers—blending physical infrastructure with digital layers of information.

As these campus wetlands mature, they're generating unexpected research opportunities. One West Coast university discovered that their system had become an important stopover for migratory birds, leading to an ornithology department collaboration. Another found that certain wetland plants accumulated pharmaceutical residues in measurable patterns, opening new avenues for contaminant tracking studies.

The movement shows no signs of slowing. With each graduating class, more students take their wetland experiences into diverse careers—from environmental law to landscape architecture. These miniature ecosystems prove that sometimes, the most powerful lessons come not from textbooks or lectures, but from getting your hands wet—quite literally—in the learning process.

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025

By /Aug 18, 2025